Play recording: Úna Bhán

view / hide recording details [+/-]

- Teideal (Title): Úna Bhán.

- Uimhir Chatalóige Ollscoil Washington (University of Washington Catalogue Number): 850403; 853910.

- Uimhir Chnuasach Bhéaloideas Éireann (National Folklore of Ireland Number): CC 018.004.

- Uimhir Roud (Roud Number): none.

- Uimhir Laws (Laws Number): none.

- Uimhir Child (Child Number): none.

- Cnuasach (Collection): National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin.

- Teanga na Croímhíre (Core-Item Language): Irish and English.

- Catagóir (Category): lore; song.

- Ainm an té a thug (Name of Informant): Joe Heaney.

- Ainm an té a thóg (Name of Collector): Séamas Ennis.

- Dáta an taifeadta (Recording Date): 1942.

- Suíomh an taifeadta (Recording Location): Carna, County Galway, Ireland.

- Ocáid an taifeadta (Recording Occasion): private.

- Daoine eile a bhí i láthair (Others present): unavailable.

- Stádas chóipcheart an taifeadta (Recording copyright status): unavailable.

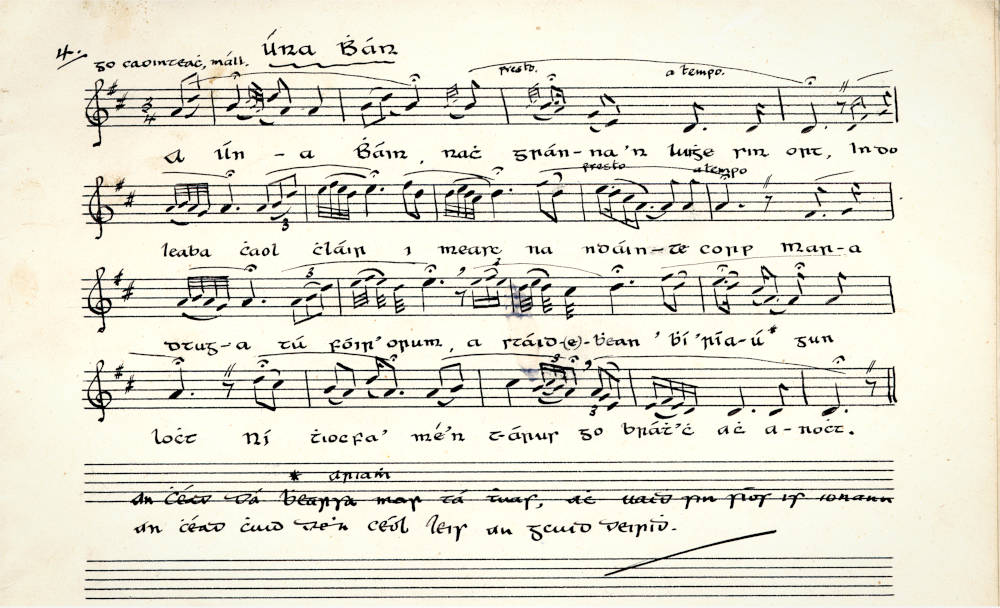

Séamas Ennis’ transcription (original handwritten document)

Úna Bhán was called Úna Mc Dermott, her name was, and she lived on an island in Lough Measc on the west coast of Mayo. Now she was in love with man called Thomas Costelloe… ‘Strong Thomas’ they called him, because he was very strong. And she fell in love with him at the fair in Ballinrobe… which is in Mayo, too… one day. They were wrestling. There was a big wrestler from England came to challenge all comers to wrestle. And nobody would fight him only Strong Thomas, they called him… he was only eighteen at the time.

And the way they used to wrestle that time: they made a circle… about eight feet wide on the ground, and the two men stood inside it, and they tied them round with belts. And then they asked them to start fighting, or wrestling. So they tied the Englishman to Thomas, and then they told them to start wrestling, and the Englishman didn’t move. And the referee told them again, and the Englishman didn’t move, and they went and took off the belts, and the Englishman fell down dead. His back was broken on the first pull from Thomas. Úna was there with her father, she fell for him. She went home…

LS: Is this all in the song?

JH: No, this is the story leading up to the song.

LS: Oh. Is this true?

JH: This is true. This is absolutely true.

LS: When did [inaudible]?

JH: Eighteenth century. The latter part of the eighteenth century.

They went home… the father and Úna. Her mother was dead. And Úna went on her bed, and fell sick. The doctor was called. Her father was a well-to-do man, and the doctor told the father he didn’t know what was wrong with her. There was nothing wrong with her, he said, as far as medical science could cure. He said there was something else wrong with her. She was pining away.

And finally, the woman who was looking after her told her father that she was pining for Thomas Costelloe. And the father hated him, you see, because he was poor. So finally, to satisfy the daughter, he sent for him. And the minute he came, that very same day, she got out of bed, and started living a normal life, eating normally. And he stayed for a week, and she was as good as ever. And then the father told him he’d have to go. She’s well now, you go your way and stay away… don’t come back any more

… And he said… and Úna was listening… If I go away

, he said, if I leave this house, if I cross that river… the Danóg River

, he said, if I cross that, I’m not turning back. But if you call me before I cross it, I’ll turn… I’ll come back

.

So he stayed for three hours, they say, he stayed on the bank of the river… he wouldn’t cross it. And no word came from the house. And he crossed the river, eventually; and the minute he crossed the river, the woman who was looking after Úna came down, calling him back. Come back!

she said. Úna wants you and her father wants you, he said, I won’t break my word. I won’t come back

.

So he went home, broken-hearted. And she died three weeks afterwards. And she was buried on an island in Lough Measc. And every night he swam the lake, the water, to sing on her grave, lament on her grave. And the third night [inaudible] she got up and gave him a slap on the cheek, and said, When you could have saved me, you didn’t. Now go home, and live your miserable life to yourself. So he went home, and six months after, he was dead, too; and he was buried beside her on Lough Measc.

LS: So what does the song say?

JH: The song… the praise he had, you know. And if she heeded him, instead of heeding her father, you know… if she ran away with him when he asked her, instead of trying to satisfy her father and at the same time ruining his and her own life, you know. She was oppressed [?] these things. He compared her to the rose in the garden, you know, and he compared her to a little flower trying to get out of the weeds and… live a life of his own. And he said, It’s an awful way you’re lying there, Úna. You’re lying there

, he said, amidst thousands of corpses. But if I knew that would happen to you, I would have turned back. I wouldn’t have… I’d have broken my word and come back to you

.

A Úna Bháin, is gránna an luí sin ort

I do leaba chaol chláir i measc na dtáinte corp

Féach, a mhná, cé b’fhearr ná an t-ochón sin

Aon ghlaoch amháin ‘gabháil Áth na Donóige.

A Úna Bháin, ba rós i ngairdín thú

Ba choinnleoir óir ‘gabháil romhan sa mbóthar thú

Ba cheiliúr is ba cheolmhar ag gabháil an bhealaigh seo thú

Mo léan dóite níor pósadh le do ghrá geal thú.

Dá mbeadh píopa fada cailce a’m is tobac a bheith ann

Tharraingeoinn amach é is chaithfinn de mo sháith

‘Maith a d’inseoinn-se dhaoibhse cé gcónaíonn Úna Bhán

I gCill Bhríde i gcrích Mha Chill, mo chreach is mo chrá.

Tá an sneachta seo ar an lár, tá sé dearg le fuil

Ach samhail mo ghrá ní fhaca mé in áit ar bith

Féachaidh-se a mhná, cé b’fhearr ná an t-ochón sin

Aon ghlaoch amháin ‘ghabháil Áth na Donóige.

What he said there, “Wouldn’t it be better, now, to give me one call crossing the Danóg River, than to be crying forever [and for] somebody to die because of it?”. Now, that’s the old way1.

Translation

Fair Úna, that’s an awful place you’re lying,

in your narrow wooden bed among a multitude of corpses.

Look, you women, wouldn’t one shout [to me] crossing the Danóg ford

be better than all that lamentation?

Fair Úna, you were a rose in the garden;

you were a golden candlestick going before me in the road;

you were a celebration — you were song and music going along the way;

my fierce sorrow that you were not married to your true love.

If I had a long clay pipe and tobacco in it,

I would pull it out and smoke my fill;

it’s well I would tell you where fair Úna lives

In Kilbride on the border of Machill, my destruction and desolation.

The snow is on the ground, it is red with blood

But the likes of my love I see nowhere.

Look, you women, wouldn’t one shout [to me] crossing the Danóg ford

be better than all that lamentation?

Notes

1. By ‘the old way’, Joe means the way they sang the song at home. He also occasionally sang what he called ‘the popular version’, by which he meant the version printed in songbooks and taught in schools. Joe had two versions of a number of the songs in his repertoire — Róisín Dubh, Casadh an tSúgáin, An Sail Óg Rua and Bean Dubh an Ghleanna for example — and he was interested in this variability; sometimes asking audiences to let him know which version they preferred.

While Úna Bhán appears on four of Joe’s commercially-available recordings, the double CD of his Gael-Linn recordings, Seosamh Ó hÉanaí: Ó mo dhúchas (CEFCD 191), includes particularly good sleeve-notes and is currently available at time of writing (Spring 2020).

The musical transcription given above was written by Séamas Ennis for Coimisiún Béaloideasa Éireann (the Irish Folklore Commission) in 1942 and was based on Joe’s singing. On that occasion, Joe told Ennis that he had learnt the song from Seán Choilm Mac Donnchadha, who lived next door to the Heaneys in An Áird Thoir. The Cartlanna are grateful to Cnuasach Bhéaloideas Éireann for permission to reproduce the document (CBÉ manuscript 1280: 327–8) here.

In his comprehensive review of the CD The Road from Conamara, the late Tom Munnelly observes that because of the sweep of its air, [Úna Bhán] is a difficult song to sing and has suffered greatly from singers who have abandoned the delicate text in order to impress listeners with operatic performance

. But this is Joe Éinniú and he’s is at his best here; bringing out every nuance of the lament with a sensitivity and artistry seldom heard.

For additional verses and discussion, see an tAthair Tomás Ó Ceallaigh, Ceol na n‑Oileán (Dublin, 1931), 15–16 and notes; also a book-length study by M. F. Ó Conchúir, Úna Bhán (Indreabhán, 1994).